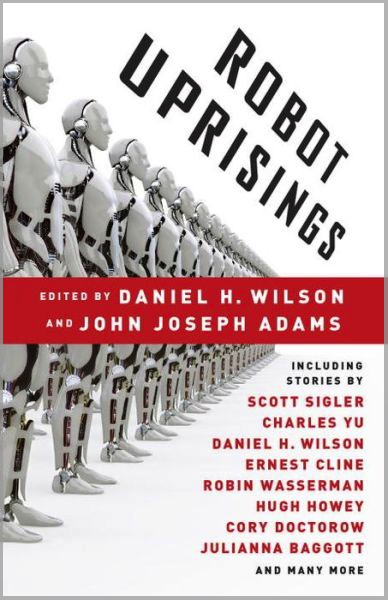

Humans beware. As the robotic revolution continues to creep into our lives, it brings with it an impending sense of doom. What horrifying scenarios might unfold if our technology were to go awry? From self-aware robotic toys to intelligent machines violently malfunctioning, Robot Uprisings brings to life the half-formed questions and fears we all have about the increasing presence of robots in our lives.

With contributions from a mix of bestselling, award-winning, and up-and-coming writers, this anthology from editors Daniel H Wilson and John Joseph Adams meticulously describes the exhilarating and terrifying near-future in which humans can only survive by being cleverer than the rebellious machines they have created.

Robot Uprisings is available April 8th from Vintage Books. Read an excerpt from Daniel H Wilson’s novella “Small Things”—one of the stories in the anthology—below!

1

In my memory, the cleanroom floor is impossibly white and smooth and unblemished. Nothing dirty, nothing natural. That hazy nebula of dust and microbes and pollen in which we all live and die has been scrubbed away. The skin of reality is peeled back to expose the raw aching bones of light and sound. It’s just hard physics that’s left, needling into your eyes and ears from some place where it’s been folded up tight and sharp-cornered and invisible.

Life in the cleanroom is an equation. The only error is human error.

The memory of what happened in there sank its barbs into me. At the emergency room, after it was over, the nurses figured out pretty quickly that I had been drunk. Once that got out, the media did not take it easy on me. Neither did the jury. I went to prison for three years. Five years after that, the cold metal of the memory is still with me, writhing under my skin with every beat of my heart.

No matter what, my wife used to say, you can’t smell nanomachinery. She was a scientist, like me, and she knew for a fact that human beings don’t have olfactory receptors capable of detecting the presence of nanomachines. That’s just the physics of it. You can’t know you’ve inhaled the nanomachines until it’s too late. Science says so, anyway, and it doesn’t give a damn what any of us thinks.

In the industry, the nanomachines we worked with were called “cretes.” Every crete is its own robot, just a couple of nanometers in size, designed to wriggle into the seams of things—into the nitty-gritty nooks and crannies of reality. They work from the inside out, rearranging individual atoms with submicroscopic precision. Together, a million cretes might form a single mote of gray dust. Not much to look at, but plenty of potential.

The potential to do good. Other potentials.

Cretes are legion. And each individual fulfills its purpose with gusto. Goal one: recognize a useful substrate. Two: selfreplicate to a tipping point. And three: rearrange the substrate to solve a problem. Water into wine. Carbon into diamond. Create a desired outcome. Each crete wants to make relentless order out of a world in chaos.

And God help anybody who gets in the way.

Up close and wide-eyed, watching a crete work is like witnessing a magic trick. Say you drop a purification crete into a bucket of toxic sludge. For a few seconds, nothing happens. Nada. This is the long flat part of an exponential curve. Cretes are doubling and then doubling again and again and… then the water goes clean, like flipping a switch. Look away, you’ll miss the miracle. The curve hits a flash point and bang.

“It’s alive!” as a guy in a lab coat once shouted.

But somebody has got to catch that monster when it escapes from the laboratory. Throw a slab of timber across the portcullis and light a torch. That was my job. I specialized in stopping the miracle. At cocktail parties, I used to say, “The water in the jug can turn to wine, but let’s not drink the whole damn ocean.”

Polite chuckles.

My cretes didn’t play nice. Every one of my babies—and there were trillions—would lie in wait for other cretes. On contact, they would identify an enemy crete variety and trick it into triggering a false positive for mutation. When you selfreplicate by the millions, every copy has to be perfect. The slightest mutation means self-annihilation. So, my invention convinced other cretes to commit suicide.

I called it creticide.

2

After the accident, I was pretty sure the world had left me behind. My life had fallen into a dull comfortable routine of failure, self-neglect, and despair. Yet when the army called, I didn’t hesitate. Not for a second. The plane tickets arrived in a thin manila envelope, and the next day I boarded a flight down to Florida.

I guess I hoped I might have a destiny after all.

This morning, I washed my hair with waxy hotel soap, then went outside and waited on the curb in the cold dawn air under a buzzing streetlight, my mind humming along with the lamp in idiot synchronicity.

I wonder again what the military wants with a guy like me.

An anonymous black sedan slides up. Government plates, tinted windows. The long car purrs beside me for a moment, hood glistening with morning dew. The driver is a ramrod of a man, sitting straight as geometry in an uncreased military uniform. Cloaked in pointless camouflage, he stares directly ahead. Doesn’t speak to me. Doesn’t look at me.

That’s not the reason I hesitate before getting inside. What gives me pause is the fact that Ramrod here has a stubby, carbon-black battle rifle dimpling the plush leather across the front passenger seat. It puts a little stutter in my step. But I get in the back and carefully buckle myself in, eyes boring a hole through the seat in front of me where I know that rifle is.

Once upon a time, I would show up to work and slip on shoe covers and a hairnet, stomp the debris mat, slide on two pairs of latex gloves, a hood, boots. Snap my goggles into place. I’d wrap myself in crinkling white butcher-paper coveralls and check myself in the mirror for fatal flaws. If I was feeling extra cautious, I’d sometimes grab a respirator and it would be just my goggled eyes swimming over two saltshaker cans in the mirror. Then the crucial last step. The coup de grace, right? Arms out, legs apart, so a technician can coat my hands and feet with my own scientific specialty—quick bursts of aerosolized creticide.

Time to go to work. Time to protect the world from the future.

Looking back, I see now I was kidding myself. The pore on a human forearm is, on average, fifty microns wide. That’s a superhighway to a crete. Cretes will float through clothes fabric like wisps of cotton through the Grand Canyon. And don’t even talk to me about the mouth and eyes or any other mucous membranes.

I fooled myself every day back then. But maybe I can fight through that bright cold memory. Sitting in this car, I’m thinking that maybe I can fool myself again.

After half an hour, the driver takes us through a quick checkpoint and we enter a military base. He leaves the main road and hits a wide-open tarmac, the whole car humming, tires singing. We weave between plodding yellow tractors and zipping military jeeps. The howling of airplane engines drowns out the coughing bark of construction equipment. Colors and sounds hammer at the tinted windows in waves of titanic, meaningless movement and noise.

It looks like progress.

“Where are we headed, exactly?” I ask the driver, expecting no response and getting none.

Ahead of us, the paved plain stretches out to the horizon. We are passing bigger hardware now, neat rows of dusky armored personnel carriers, their metal-plated chins held high, peering down at us through bulletproof window slats. The driver tugs on the steering wheel and we race toward a maze of government prefab buildings. Windowless rectangular trailers, arranged in trim grids, their retractable metal stairs lightly scratching the pavement.

The car lurches to a neat stop. The driver’s eyes flash at me in the rearview. He cuts the engine.

“So, uh, what’s the rifle for?” I ask.

His eyes flicker to me, then away. The engine ticks while he thinks about whether or not to respond. Decides to.

“In case you ran,” he says.

The driver starts the car again and puts it in drive, his foot resting on the brake. I shrug, crack my door, and step out into the lancing sunlight and pollution-sting of the wind. The sedan pulls away.

The trailer complex is surrounded by mounds of supplies stacked on wooden pallets. Cases of bottled water swaddled in distended plastic wrap, stacks of identical white cardboard boxes, sedimentary layers of bulging green duffle bags—all of it packed neatly and crisscrossed by tight tan straps. Armored forklifts are collecting and transporting the supplies in a rugged ballet.

The door to the nearest prefab opens.

An older man wearing a crisp military uniform steps out onto the flimsy stairs. The camouflage pattern on his outfit is a new one to me. It shimmers with some kind of fractally pixelated pattern cooked up by a computer and printed on hologrammatic material.

My eyes try to cross and instead I force them up to his face. He’s got a crescent of tanned scalp chasing trimmed gray hair. A pair of metal eyeglasses sinks into the skin over his ears. His hands are placed awkwardly on his hips, right pinky finger curled to avoid touching the stiff fabric of a brand-new holster, complete with a dull black sidearm.

I get the feeling he doesn’t wear this uniform often. Or maybe this is his first time.

“Colonel?” I shout over the engine noise.

He blinks at the milling, roaring airplanes, pushes his glasses up his nose, and takes a step down. Nods at me and leans over to give my hand a brisk shake. He shouts something incoherent over the racket, doesn’t smile. Motions me up the stairs.

The colonel shuts the hermetically sealable door behind us. As it closes, it sighs, leaving my ears ringing in the silence. It’s like a classroom in here, just a table, a chair, and a chalkboard. I can feel the skin on my face tighten in the blisteringly cold air-conditioning.

“Thank you for coming… ah, doctor,” he says. “Please, pardon the chaos.”

“It’s fine, colonel. I just didn’t realize you were on active duty. I thought this interview was for laboratory work.”

“I’m a professor at the United States Military Academy. Technically, we’re always on active duty.”

My face must be blank.

“West Point,” he adds. “Until recently, I was teaching mathematics and updating the latest edition of a textbook I coauthored.”

“So, you’re a colonel of math?”

“Nanorobotics, actually,” he says.

The colonel pulls some kind of eyepiece from his shirt pocket. He takes a few small steps closer to me and holds the eyepiece out like a shot glass. Shakes it.

“Would you mind if I… ?” he asks.

“Is that a pocket microscope?”

“If you would just roll up your sleeve a bit,” he urges.

After the incident, there wasn’t a single person in the nanotech field who would willingly be seen with me, much less hire me. Most of my former colleagues have made it clear that they would rather I were still in prison for what I did. Whatever kind of job the army has for me, this is my one and only chance back in.

I pull up my suit jacket sleeve.

The colonel leans over, peering into his little metal cylinder. The cold ring presses against my forearm. I can see the colonel’s lips moving as he lifts and presses again on several different spots.

“Small. Smaller than average,” says the colonel, standing and slipping the eyepiece back into his pocket. “Good for you.”

“My arm?”

“Your pores,” says the colonel. “They’re smaller than most people’s. Didn’t you know that? You should be thankful. Every micron counts.”

“And why’s that?”

The colonel of math steps away. Walks to the other side of a shining, laminated table. He puts his knuckles down on it, leans forward, and hangs his head. Takes a deep breath.

“Your creticide works, doctor,” he says.

“Against what?” I ask. “It’s useless outside of a cleanroom.”

“Things have progressed considerably in your absence.”

The colonel turns to the chalkboard. He produces a piece of chalk so naturally that it puts to rest any suspicion that he isn’t really a teacher. On the board, he sketches a lopsided circle.

“Caligo Island. Twenty miles in diameter. A thousand miles south of Africa. Thirty-five hundred miles east of South America. And those are the nearest continents. Completely isolated, thankfully.”

The colonel marks an X in the middle of the island. In short frenzied bursts, he draws vectors out of the crossed marks. Short arrowed lines that together form a gentle curve that sweeps over the southern half of the island, then out to sea, where it dissolves in scribbles.

“We have a small problem,” he says. “Well, ah, a lot of small problems. All of them located on Caligo. And unfortunately poised to spread farther.”

The vectors remind me of something. Dispersion patterns. Like the flow of dust from a broken vial. A spreading surge of blood. Crumpled forms lying still on the floor under the vacuum scream of an air purifier. The thought makes my knees go slack.

“What have you done?”

“Ah, so, it bears mentioning that it wasn’t me. In fact, I am rather far down the line of those who have been assigned to sort out this problem. My predecessors failed to meet the challenge, as it were. But you were my idea. And regardless of what has already happened in the past, to either of us, this is my… our… problem, now.”

“The original creticide patent is ten years old, colonel. My research ended years ago. Definitively. I doubt it’s good for much. Even if you poured a whole garbage can full of it—”

“Dump trucks.”

“What?”

“We use your invention by the planeload, doctor. The planes are loaded with dump trucks. You have already saved more lives than you will ever know,” says the colonel, his eyes wide and bloodshot. His bottom lip quivers and he clears his throat. “Now you will have the opportunity to save more.”

“This isn’t a spill,” I say. “Somebody is using cretes as weapons? Is this a terrorist thing? An international conflict?”

“Oh no,” he says. “We are dealing with a single man. A brilliant man—I cannot stress that enough. He is one of our best and brightest. An incredible internal asset. Truly visionary. His name is Caldecot.”

It’s a military research facility. The vector lines describe cretes escaping into the wind, infecting the rest of the island. Cretes exposed to the open air. Possibly weaponized. Lethal either way.

My hearing fades and is gone, replaced by the singing of blood as it courses through my brain. I can see the colonel’s lips moving. Slowly, his words come back into focus.

“…figured out the crete engine. Dr. Caldecot’s recipes can put holes in titanium. His specialized crete varieties can rearrange the atomic structure of almost any substrate into more useful configurations. Plain dirt into Chobham tank armor. Vegetation into trauma field supplies. An amazing breakthrough. Certainly, the technology has gotten away from him a bit. But we can help him fix this. Caldecot can put this situation back under his steady hand…”

The armed mathematician continues to speak, but my eyes return to the chalkboard. To the simulation of airborne particle spread.

“Nuke it,” I say. “Now. Before it gets off the island.”

“Not a bad suggestion,” responds the colonel, surprisingly calm. “It is certainly being considered. The problem is that the shock wave could eject unwanted material into the troposphere. A rogue cloud of aerosolized nanomachines would be a highly negative outcome. Rather than take that risk, we need simply to shut it down. Contain the problem and go back to the way things were before.”

The colonel is methodical. Clipped. His small mind works like a compact motor. The perfect man for a job like this. He doesn’t understand enough to panic. I close my eyes and concentrate on breathing. Open them to white lines on black chalkboard.

I think maybe I’m looking at the end of the world.

The entire prefab shudders. The plane engines outside are getting louder. I notice there are no windows in this tiny vibrating room.

“We need you to go there,” says the colonel. “The army has established a beachhead outside the perimeter of… the worst of it. A portable laboratory is waiting for you. State of the art. You will collect samples of the cretes that have gone feral. You will adapt your creticide to destroy the central machinery of the various varieties you collect.”

“You want me to go there?” I ask, lips numb.

“Yes, well…” He sighs, then continues, speaking slowly. “We can’t risk taking the cretes off the island… so I’m afraid we’ve got to bring you to them. You will of course be well compensated.”

The trim little soldier is like a machine, spitting out facts with no concept of what they mean. I wonder what a man like this sees. What color does the flush of fear on my cheeks appear to him? Gray, I imagine. Gray as an equation.

“I’ll die,” I say.

“That’s not a certainty,” he says. “Besides, in your case, after everything that’s happened… don’t you feel that you owe some kind of… a debt?”

The memory is as bright and hard as white tile.

“I went to prison, colonel. I paid my debt. In more ways than you can imagine,” I say, voice rising over the racket outside. “My answer is no. No fucking way. Thank you for the invitation and I really appreciate the opportunity and all, but there’s just no way. It may be hard for you to believe, but I don’t want to die.”

“Ah, boy,” says the colonel, sitting down on a thin plastic chair. It strikes me that everything in this room is made of lightweight plastic. Even the trembling walls. The colonel’s fatigues crease stiffly at the knees when he sits. It’s familiar, somehow. A tendril of fear is wriggling up from my belly and into my chest.

It’s creticide. I think the colonel’s clothes are coated in creticide. The coup de grace, right?

“This is the awkward part,” says the colonel.

Outside, the noise surges even louder, rattling the door frame. It’s a howling thrum that seems to come from the center of my head, causing my teeth to chatter. My vision dances with each shivering pulse. Something big shoves against the trailer from outside, and I stumble, arms out to catch the door.

“Good luck, colonel. Good-bye.”

The colonel shows me his palms and shrugs. “Thank you for your service.”

I yank open the flimsy door, half expecting it to be locked. I’m on the retractable landing before it dawns on me that I don’t understand what I’m seeing.

A soaring wall of tan fabric mounted between curved ribs of steel. Flip-down metal seats mounted to the wall, folded upright and erect, their loose seatbelts flopping like untied shoelaces. The line of seats is broken only by a small oval door with a long metal handle. Glowing red lightbulbs illuminate the narrow passage. Stenciled on the door are the words Only Qualified Personnel to Open Mid-Flight. C-5M Super Galaxy.

I am in the belly of a C-5M transport aircraft.

“You see, we are already on our way,” says the colonel, producing a metal flask. He looks smaller now, silhouetted in the shaking doorway. The vibration recedes as our wheels leave the ground and his voice is suddenly louder. “Ah, don’t forget… every micron counts.”

And the colonel kicks the door shut in my face.

3

“Okay, you guys. Okay. What’s the situation? What are your orders? Do you have some kind of a dossier I can look at?” I ask.

The young man stares at me for a couple of reptilian blinks. Then, a smile trampolines to the corners of his mouth. The red interior lights of the transport plane glint darkly from his creticide-coated army fatigues. “Did you say a dossier? He’s asking me for a dossier?”

After a few minutes cursing outside the colonel’s locked trailer, I began creeping down the narrow corridor studded with flip-down seats. The plane’s center aisle was loaded with wooden crates covered in netting. An armored trapdoor that seemed to lead to the cockpit was locked, my knocking ignored.

I heard laughing and smelled cigarette smoke before I saw them near the back of the plane. About a dozen young men dressed in military uniforms, sprawling over the foldeddown seats. Most were asleep or pretending to be, their boots up and resting on crates across the narrow aisle. Crimsonkissed silhouettes.

But these two were awake. Private Tully and Sergeant Stitch.

“Yeah, a dossier. Some kind of report,” I say. Tully looks at me with round glassy eyes, his smile like a gash in his face. “Look, I’m the crete expert,” I say. “They called me in to fix whatever the hell has gone wrong down there. Help me do my job. Does anybody here know anything?”

Tully is seized with giggles, compulsively scratching the back of his crew cut with a bony hand. I frown and look at the other paratrooper sitting next to him, the one called Stitch.

“What’s wrong with him?” I ask.

Stitch’s face is slack, almost paralyzed. “Jesus, man. You’re not the first,” he mutters slow, not looking at me. “We’re not the first. Not the last. Not even close.”

Tully pulls his lips apart expectantly. Inside his mouth, milky-white teeth are mottled with dark spots. Pieces of metal filling, silvery. “Did you think we were it, man?” he asks. “Did you think we were like a crack squad or something? Huh?”

He swallows and puts on a serious face.

“Roger that, sir. United States Marine Force Recon, special technological retrieval and recovery operational detachment reporting. Rest assured that we will handle this situation, sir. Handle it! We will fucking handle the shit out of it!”

The giggler goes back to scratching the back of his head, fiercely.

“Handle? We broke the handle off,” mutters Stitch, smiling to himself. His eyes are closed now. His fleshy cheeks quiver with the mechanical vibration of the cargo plane.

“How many others have been sent?” I ask. “What’s the situation?”

“Oh shit,” says Tully, sitting up, eyes wide. “He wants to know the sitch, Stitch. Hear that? The sitch, Stitch.”

Stitch won’t respond. Or can’t.

“Thanks,” I mutter, weaving my way back up the aisle, wading through the murky red glow of overhead lights. When I can’t hear the laughing anymore, I collapse onto a folding wall-mounted chair. Shut my eyes.

I can feel the darkness outside the plane. The raw infinite space. It should stay empty, I find myself thinking. Everything is red in this booming cavern, and I’m starting to feel like I’m going blind. I’m in a metal tube screaming toward the epicenter of something very, very bad. Acid lingers in the back of my throat.

Those faint giggles keep coming, mechanically, and I understand now they’ve got nothing to do with humor.

Eyes squeezed shut, I rest the back of my head against the fabric skin of the wall. Focus on the vibration, the cold air breathing over the nape of my neck. I try to let the repetitive wailing of the engine smooth out the edges of my fear. After a few minutes, it starts to work.

“Hey,” whispers someone, and I startle. Private Tully’s face is inches away from mine, his breath hot on my cheek. “Let me show you the sitch, Stitch. Take a look-see.”

The young paratrooper leans forward, still rubbing the back of his head. When I see what he is scratching at, I hold my breath and ease away from him. I should close my eyes, too. Any mucous membrane is an entry point for a crete. But I can’t look away from the deformity.

It’s beautiful, in a way. The tooth. A tiny white bud. Perfectly formed calcium growing from the back of his skull. The imprints of surrounding molars are dimpled knuckles under his skin.

It’s probably not contagious, since he’s still alive. The crete must have been designed to grow spare teeth for dentists. It’s all I can think of. I didn’t know it was possible. The crete borrowed some calcium from his skull and rearranged it. Part of me wants to harvest a specimen. Another part wonders how badly it hurts.

Tully’s voice is muffled, his head down, words swallowed by the rumble of the plane. “It’s the small things,” he says. “On Caligo, you got to be sure and watch out for the small motherfuckin’ things.”

Giggles.

I unstrap my seatbelt and get up without a word. Go for a long walk around the humming belly of the plane. Try to work the dread out of my belly. That soldier should be in a hospital, not sent back into service. But we’re both on our way to Caligo: an infected soldier and a broken scientist. It smells like desperation.

After a while, I find a coffeepot strapped to the wall and pour myself a cup. Find another seat by myself. Sipping coffee, I look out the window and try not to shake. Some city is sprawled out far below. A gleaming explosion, spreading its smoldering tendrils across cold earth.

Light eating the darkness.

The barbed memory appears unannounced, as it always does. That morning my head was tucked under the ventilation hood. The rush of air in the cleanroom was hypnotic. I remember being hungover from the night before, watching my gloved hands at work, thinking about whether or not I should have had a beer and a shot for breakfast. My wife was across the room, working at her station with her back to me. We hadn’t been speaking much.

The vial fell.

More accurately, I dropped it. Being a little drunk, I hadn’t bothered to activate the plastic shield that was supposed to cradle my arms. The finger-sized cylinder was made of inert hardened glass, but it took a bad bounce and the lid shattered on the outer lip of the hood. The vent pulled in part of that puff of concentrated crete dust in a swirling arc that moves slowly in my memory, like the spread of a galaxy. But the rest of the dust was thrown out into the room in a fine expanding powder.

I remember touching my face by instinct to secure my respirator. The baffled plastic was there and ready. I had put it on to hide my beer breath from my wife. The drinking had been getting out of control, and I knew it, but it didn’t scare me. I had only felt curious about how far it would go. That respirator was the reason that I recovered after two weeks in the hospital, instead of bleeding to death from the inside out.

For a moment, the other scientists stood oblivious at their stations. Then a panicked scream muscled out from under my respirator. My wife half turned to face me, her thin arms out and holding a pen and clipboard. A lock of blond hair had escaped from her paper hat and hung curled behind her ear. Seeing my wide eyes and empty hands, she flashed her teeth, nostrils flaring as she drew a sharp intake of breath. An autonomic startle reaction. Designed to increase oxygen flow to prepare the body for fight or flight.

Evolution is so slow to catch up with technology.

While I was yelling in half-drunken fright, all three of my labmates were inhaling airborne particles of an experimental self-replicating creticide variety down their windpipes. The cretes were immediately embedded into the soft tissue of their lungs.

Christoff ran for the door. It was locked. Shoulders slumped, he kept rattling the bar up and down. The panicked synapses of his brain were stuck in a loop. Jennifer stood frozen, her mouth moving, repeating the same words over and over: “You fucker. You stupid fucker.” She knew what was coming and she had never liked me anyway.

But my wife just stared, hands over her stomach. Pen and clipboard fallen to the tile. Her blue eyes were sad and round. They were filled with tears.

And the hemorrhaging began.

I force my eyes open, snap back to the present. Outside the window of the cargo plane, the shine of that anonymous city licks the underside of the airplane wing. It paints the sobbing jet engines as they choke down the frigid night and shit out thrust and toxins and torn air. Outside, the plane and the night pound into each other. Like the surf crashing against the shore, each trying to consume the other without hunger or urgency.

Turning my face up, I stare into the dome of space. Far above, hundreds of billions of stars invade the night sky, gorging on the vastness.

Mindless, and eternal.

4

I wake up with Tully’s grinning face inches from mine.

“You’re dropping with me, doc,” the paratrooper says, shoving a harness into my lap. “Put this on and let me check it. You drop no matter what, so put that shit on tight and right if you want to live.”

Rubbing my eyes, I see it’s still night outside. A chill has seeped through the thin padding on the metal chair and through my suit pants. Standing, I stretch and stamp my feet on the metal decking, trying to get feeling back. Tully is already down the aisle, mechanically checking the chute pack of another paratrooper.

“Can I get some warmer clothes?” I call after him.

“What you got is what you got,” he says, not turning.

My response is cut off by a wall of wind. Stitch has just opened the side door, yanking a bar and pulling the whole thing in and up. Only blackness and noise is on the other side.

Hurrying, I slide into the brown harness. I tug the straps tight, ignoring my awkwardly cinched-up pants. With shaking hands, I button my pathetic suit jacket. As an afterthought, I lean over and retie my wingtips as tight as possible.

“Let’s go,” shouts Tully, grabbing my arm.

The dozen other paratroopers are lining up, lifting their belly-mounted gear bags with both hands. Stitch is at the door, shouting commands to the soldiers. They waddle like pregnant women, latching carabiners onto a sloping wire that runs down the wall.

The floor shudders and the rear bay door of the plane yawns open, revealing a grinning slice of ocean. I can see a sprinkle of stars above a purple horizon. Someone pulls a switch and pallets of supplies whip past me, inches away, rolling down and right out of the back of the plane. Falling into nothing, deploying damp parachutes that glisten like exposed lungs.

My limbs start to shiver uncontrollably.

The line of paratroopers is moving now. A round light next to the open doorway shines a steady piercing green. Stitch is methodically collecting the umbilical cables as each paratrooper steps through the door.

“Time to go,” Tully shouts over the wind.

“Wait,” I’m saying.

From behind, he yanks hard on my leg straps. My breath catches from another momentous tug on my shoulder straps. Tully latches his harness onto mine. Hands on my shoulders, he shoves me to the rear of the line. I lurch forward on my slippery dress shoes, legs numb. Then we are trotting, a shuffling column racing toward a flat purple doorway.

“Wait!” I shout, but now I can’t even hear myself over the ringing of boots on metal. I trip on my next step, feel Stitch slap me on the back of the head. There is no step after that, just wind, and my eyes squeeze closed. Twin tracers of freezing tears crawl blindly over my temples. My breath is pulled out of me and shoved back in, mixing with the bellowing atmosphere.

And finally, I open my eyes.

The island is real—a brownish scab on the broad silvery ocean. A pall of dark smoke hovers over it. The dawn sun, a pink smear sitting on a perfectly flat horizon, pushes stained fingers through the smog. It spills the rest of itself in streaks and dashes over miles of ridged waves below.

As I hang from the deployed parachute, the harness bites into my armpits. My suit is ripped, my legs dangling, pale ankles flashing. My pant legs flap in the breeze. It’s quiet now, and I hear the parachute canopy creaking in a nautical kind of way. Instinctively, I grab the strap over my chest and hold on to it with everything I’ve got.

We drift through the smoke and into the light.

The air still has a chilly edge, but I can already taste the moist tropical undertones. And something else underneath. Something burnt and coppery.

“Doesn’t look so bad,” I call to Tully.

“Even hell looks pretty from far away,” he says, as we sway together.

And then the ground is looming. Instead of a greenbrown blur, I see individual trees and military buildings. I catch flashes of detail from all over the tiny island. Far inland, there is a stone pavilion surrounded by deep jungle canopy. Radio towers sprout from a cliffside. And directly below, coming fast, is a sprawling vista of soldiers and buildings and vehicles. It’s insectile—looming termite mounds of human activity.

“Feet up,” calls Tully, and I comply.

A grassy field speeds past like a conveyor belt. Tully’s boots flare up and he plants them loosely on the grass. He runs a few steps and leans back into the parachute’s drag until we are sitting, my body buzzing with sensation, dewy grass soaking through the thin fabric of my pants.

I hear a clink as Private Tully unfastens himself from me.

Around us, the dozen other paratroopers are landing, too. Hopping up and chasing down parachutes and folding them. Nobody speaks to me. As the field clears, I wriggle out of my harness and hold it in dumb fingers. It has no more purpose, so I shrug and drop the high-tech bundle into the deep grass.

Warm sunlight winks from the metal bits as I walk away.

Small Things © Daniel H Wilson, 2014